The Usual Story With KPIs

Here’s the common story with business KPIs. You create a balanced set of KPIs to monitor the main business objectives, or the investment thesis if you’re private equity owned. They’re a mixture of leading and lagging indicators, bought into by management. They’re SMART, reported at least monthly, each has a single owner, etc, etc. The Board or management pack then explains any deviations from expected performance and lays out actions to address issues.

The big gap in all this common sense is how do you choose which KPIs to monitor. In most businesses there are dozens of things you could monitor. But you can only concentrate your attention on maybe 6 to 8 KPIs. The standard practice is to choose them based on experience and intuition, plus maybe some in vogue measure for the sector (CLV, CAC, NPS, etc). But KPIs are what you use to focus your attention on what’s most important. So your choice of KPIs makes a big difference to how successful you become. Given the stakes, there’s a better, more scientific way of choosing and evolving a set of KPIs.

A Scientific Way of Choosing KPIs

Like with most things in science, you start with your primary, overriding objective. For most businesses this will be something like making the business as valuable as possible.

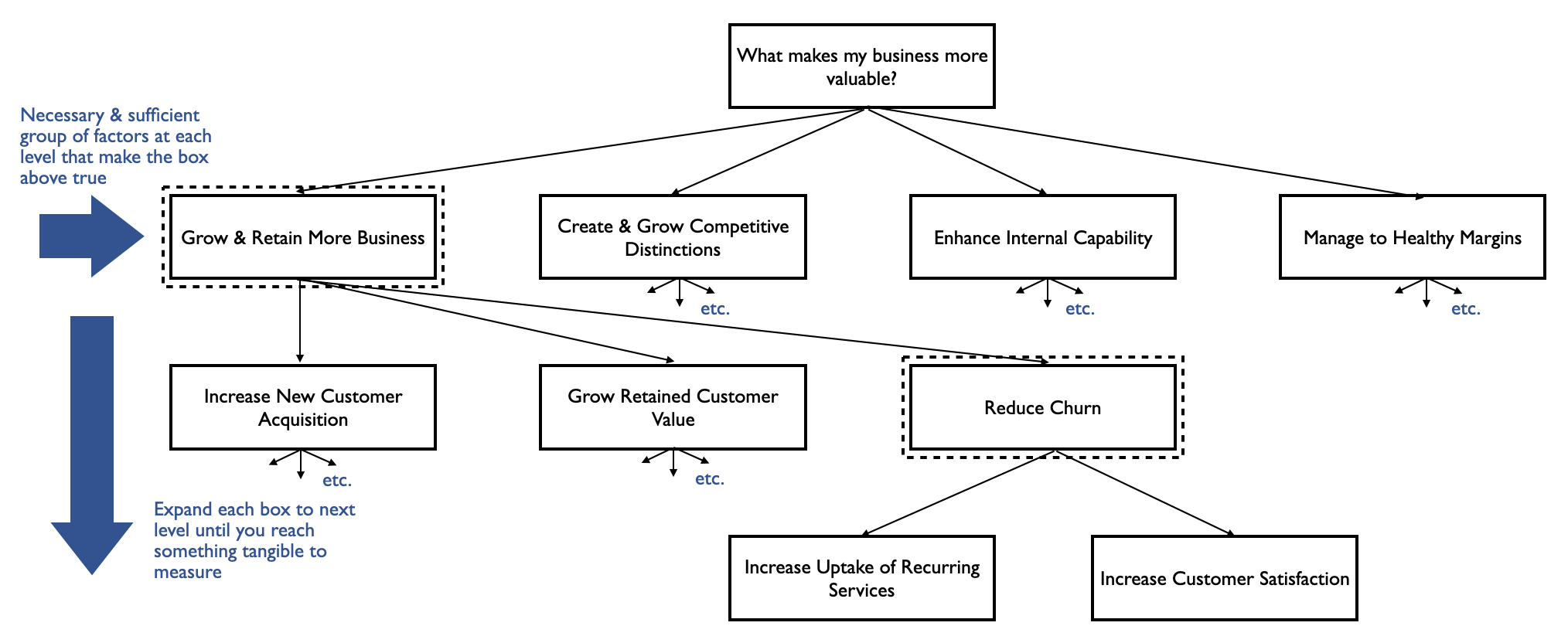

Then you break that down into a set of necessary and sufficient conditions to make that objective happen. This would look something like this.

Notice that this is a short list. You’ve only included what’s necessary. Anything nice to have but unnecessary has been culled heartlessly from this list.

Notice also that it contains no major gaps either. The set of factors needs to be sufficient to make the box at the top true.

At this high level of abstraction, the boxes are a bit generic and not much use yet. So you need to repeat the process with each box until you get to something tangible you can measure. Just expanding the first box and one of the boxes below it, this could look something like this.

You can always break each of these down further, but that’s for when you cascade your high level KPIs down to the business unit or functional team.

You’ve now got, in business and investor jargon, the set of levers you can pull to affect business value. You can’t monitor all of these actively at Board or top team level. So you need to choose 4-8, using a couple of simple criteria

- A conceivable change in the value of this measure makes the biggest difference to the ultimate objective (e.g. maximising company value). This is because it’s so tightly linked to company value (things like recurring %, churn % or reputation measures). Or it’s because it could conceivably vary by a lot (things like customer satisfaction, mega-project cost control or major contract wins)

- You’re measuring at least one thing related to each of the top level boxes

After all of this you’ll have 3-4 highish level measures that cover the top level of boxes, plus another 1-3 that live further down in the hierarchy of measures but are so important for value or are so potentially variable that they’re worth actively monitoring at top team level. Something like this:

Now you’ve got a scientifically created set of KPIs that you can link directly back to growing the value of the business. You know these are the most important things to have on the instrument panel as you steer the ship. Compare these to the ones you put together from intuition and experience. Chances are you’ll have missed something that would seriously affect the value of your business.

Post Script – Key Survival Indicators

There’s another set of measures that nearly everyone should be using. These are much more about survival, and we could maybe call them key survival indicators. Those are a subject for another article on another day, but here’s a taster. The top box now says something like, “What could kill my business before I have time to do something about it?”