Experimenting Good; Copying Amazon & Google Bad

Running constant experiments is an excellent way to navigate through a complex uncertain world. It helps keep things fresh, helps you be daring and grow, and can take out a whole heap of risk.

But if you follow the media hype [here] and copy Amazon, Google or Netflix’s relentless testing of every tiny aspect of their proposition then you’ll waste a whole lot of time and potentially a lot of money. If you follow the equally hyped British Cycling’s marginal gains philosophy, you’ll be making the same mistake.

I’ll (partly) explain why here.

We need to start by asking what makes a good experiment, which I think has 2 components. First, there’s a good cost benefit of doing the experiment at all. Second, the experiment is done well for your circumstances.

I’ll just cover the first of these, and leave the second for another day.

Cost Benefit of Doing the Experiment

Here’s what I think makes a good cost benefit in doing an experiment:

1 There’s a potentially big enough effect

2 It’s cheap, for you

3 You don’t bet the farm, i.e. there’s a small enough downside if it doesn’t work

4 It gives you information quickly, good or bad

2-4 are hopefully self evident so I just want to dwell on the need for a big enough effect. We’ve described before here why you should be using experiments to make bold moves and swing for the bleachers. But there’s even more reason to just experiment with big effects. Have a look this chart:

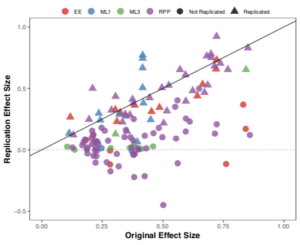

This chart was from a study of attempts to replicate experiments in the social sciences. It shows the effect size [1] in original experiments versus the effect size in attempts to replicate the experiments. The first thing to notice is that most of the points are below the 1:1 line, i.e., the effect size in the attempts to replicate is usually lower than in original experiments. The second thing to notice is that the stronger the effect size, the more likely the experiment is to replicate at all. And replication is what we care about in real life

How Some People Benefit from the Numbers Game & You Don’t

Here’s where a numbers game helps the big, highly hyped experimenters:

- If you can afford to do thousands of experiments then some of those dubious-looking low effect ones will be legitimate and replicate in real life, and you’ll be ahead despite many wasted non replications

- The benefit to Amazon of tinkering with the landing page and getting a tiny percentage increase in conversion or basket size is enormous. So even if the effect only turns out to be 1/10 or 1/100 the size in real life, it’s still enormous. The benefit of a 0.1% increase in speed for the much heralded marginal gains crew at British Cycling and Team Sky is massive in a sport where a tyre’s width wins or loses you a medal, i.e. it’s not a marginal gain at all

Most of us aren’t big enough to benefit materially from the occasional sub 1% improvement. Even fewer of us can run enough experiments on marginal gains to benefit from the odd few lucky replications. So we should do our cost benefit before we even start to gulp down the experimenting Kool Aid, and only bother with big exciting changes with potentially big effects.

[1] Effect size is a term that can mean many things in statistics. I think of it as how big an effect you observed, versus randomness or the effects of other factors that you haven’t been observing