A good way of becoming celibate is to make a point of correcting other people’s grammar. A great way to dissuade people from your argument is to make petty criticisms of the opposing side. That’s why, if you want to understand an argument, have a useful discussion, and even persuade people to your point of view, it’s important to be charitable.

Here’s what I mean by charitable. You genuinely want to understand why the other person is taking this (seemingly ridiculous) point of view. It means putting their argument in its best light, acknowledging their good points. It means giving imprecise words a positive interpretation, and letting minor inaccuracies go unchallenged.

If you’ve had the wherewithal to do that, your version of the other person’s argument should look like a good one. Or at least it shouldn’t resemble the ramblings of a lunatic that your inner uncharitable argument buster was tempted to portray.

Some Logic Busting

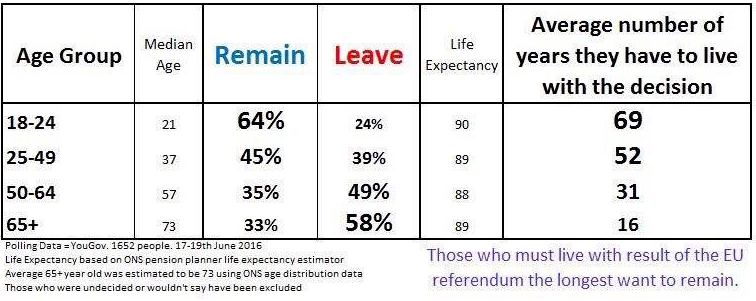

Here’s an example argument that’s been doing the rounds following the UK’s seemingly never-ending EU referendum post mortem. This analysis by the YouGov polling organisation argued young people would be hard done by a Leave vote. Under-40s quote it alongside comments about not giving up seats on buses.

Even leaving aside the clunky use of font sizes for graphical effect, logic busters tore this to pieces:

- The analysis is wrong. YouGov should have used conditional probabilities for life expectancy (your life expectancy goes up with every year you survive)

- The bands are deceptive because they aren’t the same size, especially the tiny but extreme 18-24 band

- It ignores how many from each band cared enough to vote, and it turned out that many more older people cared and voted

- The poll was from before the referendum, which YouGov called incorrectly, making them a poor source

- It assumes people don’t become continually more pro-Leave as they age anyway

A Generous Way of Stating the Argument

Instead of dismissing all arguments based YouGov’s work as pseudo-analytical rubbish, here’s the case expressed generously:

- Younger people strongly prefer Remain, and older people Leave (even if YouGov is 8% out as it was in the referendum this strong trend is still true)

- Younger people have much longer to live with the decision than older people (even if you correctly use conditional probabilities)

- We’ll grant that people may not become more EU resistant as they age

- Therefore, when you vote you should consider others who’ll be living with your decision, long after you’ve joined Elvis

I’ve ignored the criticism about band sizes because the trend is clear. Young people not turning out to vote may explain why Leave won, but that’s not relevant to the argument.

If I’ve done my job properly, the argument should now look reasonable. We should now understand the protagonist’s point well enough to get beyond Punch & Judy.

Charitable Understanding Doesn’t Mean You Agree, But It Might

You now have a chance of getting to the heart of the matter.

Do you just disagree about what’s most important (is it more important to do what you think is right, or consider the harm to others if you’re wrong)?

Are you making different assumptions (we’re still going to have freedom of movement, vs we’re going to close the borders and brick up the tunnel)?

Are you each afraid of different things (Eurocrats telling you what to do for the rest of your life, vs being free to work in Slough but not Paris)?

Or, God forbid, did you decide the other person has an excellent point that’s changed your mind (you know what, I’m going to trust my grand children on this one)?

You may still conclude that the other person is a closed-minded bigot or self-serving sociopath, but at least you learned that by not being one yourself.

The quality of your discussion just went from bickerfest to considering important nuances and beliefs. You may even make a good decision or get to the truth.